Maude Adams

Maude Adams | |

|---|---|

Maude Adams, 1901 | |

| Born | Maude Ewing Adams Kiskadden November 11, 1872 Salt Lake City, Utah, U.S. |

| Died | July 17, 1953 (aged 80) Tannersville, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | actress |

| Years active | 1880–1918, 1931–1934 |

| Partner(s) | Lillie Florence (ca.1891–1901, died) Louise Boynton (1905–1951, died) |

| Signature | |

Maude Ewing Adams Kiskadden (November 11, 1872 – July 17, 1953), known professionally as Maude Adams, was an American actress and stage designer who achieved her greatest success as the character Peter Pan, first playing the role in the 1905 Broadway production of Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up.[1] Adams' personality appealed to a large audience and helped her become the most successful and highest-paid performer of her day, with a yearly income of more than $1 million during her peak.[1][2]

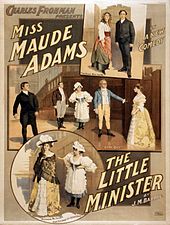

Adams began performing as a child while accompanying her actress mother on tour. At age 16, she made her Broadway debut, and under Charles Frohman's management, she became a popular player alongside leading man John Drew Jr. in the early 1890s. Beginning in 1897, Adams starred in plays by J. M. Barrie, including The Little Minister, Quality Street, What Every Woman Knows and Peter Pan. These productions made Adams the most popular actress in America.[3] Her work on these shows' production design and innovative technical lighting helped to make them a success, and she was named as inventor on three light bulb patents. She also performed in a number of other plays. Her last Broadway play, in 1916, was Barrie's A Kiss for Cinderella. After a 13-year retirement, she appeared in more Shakespeare plays and then taught acting in Missouri. She retired to upstate New York.

Early life and career

[edit]

Adams was born in Salt Lake City, Utah Territory, the daughter of Asaneth Ann "Annie" (née Adams) and James Henry Kiskadden. Adams's mother was an actress, and her father had jobs working for a bank and in a mine.[4] Little else is known of Adams's father, who died when she was young.[5] James was not a Mormon, and Adams once wrote of her father as having been a "gentile". The surname "Kiskadden" is Scottish. On her mother's side, Adams's great-grandfather Platt Banker converted to Mormonism and moved his family to Missouri, where his daughter, Julia, married Barnabus Adams. Barnabus and Julia then migrated as part of the first company to enter the Salt Lake Valley with Brigham Young in 1847, where he cut timbers for the Salt Lake Tabernacle.[6] Adams was also a descendant of Mayflower passenger John Howland.[7]

Adams appeared on stage at two months old in the play The Lost Baby at the Salt Lake City Brigham Young Theatre.[8] She appeared again at the age of nine months in her mother's arms. Over her father's objections, Adams began acting as a small child, adopting her mother's maiden name as her stage name. They toured throughout the western U.S. with a theatrical troupe that played in rural areas, mining towns and some cities.[4] At the age of five, Adams starred in a San Francisco theater as "Little Schneider" in Fritz, Our German Cousin and as "Adrienne Renaud" in A Celebrated Case.[2] At the age of nine, Adams lived with her Mormon grandmother and Mormon cousins in Salt Lake City while her mother remained in San Francisco.[9] It is not clear whether she identified as a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as her mother did. She was never baptized Presbyterian, although she attended a Presbyterian school.[9] Later in life, Adams took long sabbaticals in Catholic convents, and in 1922 she donated her estates in Lake Ronkonkoma, New York, to the Sisters of the Cenacle for use as a novitiate and retreat house.[10][11] She never converted to Catholicism or discussed the topic in any interviews.[9]

Adams debuted in New York at age 10 in Esmeralda and then returned briefly to California. She then returned to Salt Lake City to live with her grandmother and studied at the Salt Lake Collegiate Institute.[4] She later wrote of Salt Lake City: "The people of the valley have gentle manners, as if their spirits moved with dignity."[6] Adams also later wrote the short essay "The One I Knew Least", where she described her difficulty in discovering her personality because of playing so many theatrical roles as a child.[4]

Early adult career

[edit]

Adams returned to New York City at age 16 to appear in The Paymaster. She then became a member of E. H. Sothern's theatre company in Boston, appearing in The Highest Bidder, and then was on Broadway in Lord Chumley in 1888. Charles H. Hoyt then cast her in A Midnight Bell where audiences, if not the critics, took notice of her. In 1889, sensing he had a potential new star on his hands, Hoyt offered her a five-year contract, but Adams declined in favor of a lesser offer from the powerful producer Charles Frohman who, from that point forward, took control of her career. She soon left behind juvenile parts and began to play leading roles for Frohman,[4] often alongside her mother.[12] In 1890, Frohman asked David Belasco and Henry C. de Mille to specially write the part of Dora Prescott for Adams in their new play Men and Women, which Frohman was producing. The next year, she appeared as Nell in The Lost Paradise.

In 1892, John Drew Jr. (one of the leading stars of the day) ended his 18-year association with Augustin Daly and joined Frohman's company. Frohman paired Adams and Drew in a series of plays beginning with The Masked Ball and ending with Rosemary in 1896. She then spent five years as the leading lady in John Drew's company.[13] There, "her work was praised for its charm, delicacy, and simplicity."[4] The Masked Ball opened on October 8, 1892. Audiences came to see its star, Drew, but left remembering Adams. Most memorable was a scene in which her character feigned tipsiness for which she received a two-minute ovation on opening night. Drew was the star, but it was for Adams that the audience gave twelve curtain calls, and previously tepid critics gave generous reviews. Harpers Weekly wrote: "It is difficult to see just who is going to prevent Miss Adams from becoming the leading exponent of light comedy in America. The New York Times wrote that Adams, "not John Drew, has made the success of The Masked Ball at Palmer's, and is the star of the comedy. Manager Charles Frohman, in attempting to exploit one star, has happened upon another of greater magnitude." The tipsy scene started Adams on her path to being a favorite among New York audiences and led to an eighteen-month run for the play.

Less successful plays followed, including The Butterflies, The Bauble Shop, Christopher, Jr., The Imprudent Young Couple and The Squire of Dames. But 1896 saw an upturn for Adams with Rosemary, That's for Remembrance. A comedy about the elopement of a young couple, sheltered for the night by an older man (Drew), the play received critical praise and box office success.[14]

Barrie and stardom

[edit]

Frohman had been pursuing J. M. Barrie (the future author of Peter Pan) to adapt the author's popular book The Little Minister into a play, but Barrie had resisted because he felt there was no actress who could play Lady Babbie. On a trip to New York in 1896, Barrie attended a performance of Rosemary and at once decided that Adams was the actress to play Lady Babbie.[14][15] Frohman worried that the masculine aspects of the book might overshadow Adams's role. With Barrie's consent, several key scenes were changed to favor Lady Babbie.[16] The play opened in 1897 at the Empire Theatre and was a tremendous success, running for 300 performances in New York (289 of which were standing room only) and setting a new all-time box office record of $370,000; it made Adams a star.[17][15] It also toured successfully, running for 65 performances in Boston.[4]

Another play by Barrie, Peter Pan; or, The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up (1904), became the role with which Adams was most closely identified. She was the first actress to play Peter Pan on Broadway. Only days after her casting was announced, Adams had an emergency appendectomy, and it was uncertain whether her health would allow her to assume the role as planned. Peter Pan opened on October 16, 1905 at the National Theatre in Washington, D.C. to little success.[18] It soon moved to Broadway, where the play had a long run.[19] Adams appeared in the role on Broadway several times over the following decade.[citation needed] The collar of her 1905 Peter Pan costume, which she had co-designed, was an immediate fashion success and was henceforth known as the "Peter Pan collar".[20]

Adams starred in other works by Barrie, including Quality Street (1901), What Every Woman Knows (1908), The Legend of Leonora (1914), and A Kiss for Cinderella (1916). In 1899, she portrayed Shakespeare's Juliet. While audiences responded to her performance with standing ovations, critics generally disliked it. The critic Alan Dale, reviewing her debut in the role at the Empire Theatre, called her Elizabethan English "grotesque at times" and commented that Adams had performed with "pretty purring", not classical. On the other hand, he described her performance as "romantic", "sublime" and "not sinking beneath the waves."[21] Audiences loved her in the role,[22] selling out the 16 performances in New York.[citation needed] Romeo and Juliet was followed by L'Aiglon in 1900, a French play about the life of Napoleon II of France in which Adams played the leading role, foreshadowing her portrayal of another male (Peter Pan) five years later. The play had starred Sarah Bernhardt in Paris with enthusiastic reviews, but Adams's L'Aiglon received mixed reviews in New York. In 1909, she played Joan of Arc in Friedrich Schiller's The Maid of Orleans. This was produced on a huge scale at the Harvard University Stadium by Adams.[23][24] The June 24, 1909 edition of the Paducah Evening Sun (Kentucky) contains the following excerpt:

Joan at Harvard, Schiller's Play reproduced on Gigantic scale. ... The experiment of producing Schiller's Maid of Orleans beneath starry skies … was carried out [by] Adams and a company numbering about two thousand persons ... at the Harvard Stadium. ... A special electric light plant was installed ... a great cathedral was erected, background constructed and a realistic forest created. ... Miss Adams was accorded an ovation at the end of the performance.[25]

She appeared in another French play with 1911's Chantecler, the story of a rooster who believes his crowing makes the sun rise.[26] She fared only slightly better than in L'Aiglon with the critics, but audiences again embraced her, on one occasion giving her 22 curtain calls.[26] Adams later cited it as her favorite role, with Peter Pan a close second.

Later years and death

[edit]Adams retired in 1918 after a severe bout of influenza.[27] During the 1920s, she worked with General Electric to patent improved and more powerful stage lighting,[23] (U.S. patent 1,884,957, U.S. patent 1,963,949, U.S. patent 2,006,820) and with the Eastman Company, to develop color photography. It has been suggested that her motivation for her association with these technology companies was that she wished to appear in a color film version of Peter Pan, and this would have required better lighting and techniques for color photography.[28] Her electric lights ultimately became the industry standard in Hollywood with the advent of sound in motion pictures in the late 1920s.[29] After 13 years away from the stage, she returned to acting, appearing occasionally in regional productions of Shakespeare plays, including as Portia in The Merchant of Venice in Ohio, in 1931, and as Maria in Twelfth Night in 1934 in Maine.[4]

Often described as shy, Adams was referred to by Ethel Barrymore as the "original 'I want to be alone' woman".[30] Her retiring lifestyle, including the absence of any relationships with men, contributed to the virtuous and innocent public image promoted by Frohman and was reflected in her most successful roles. t1=Axel| title=The Sewing Circle: Sappho's Leading Ladies|date=February 2002|publisher=Kensington Publishing Corporation|location=New York City|isbn=978-0758201010|page=3| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QwxFfhiFcAAC&pg=PA3}}</ref>[31] She had two long-term relationships that only ended upon her partners' deaths: Lillie Florence, from the early 1890s until 1901, and Louise Boynton from 1905 until 1951.[27]: 16 Adams was known at times to supplement the salaries of fellow performers out of her own pay.[29] Once while touring, a theater owner significantly raised the price of tickets, knowing Adams's name meant a sold-out house. Adams made the owner refund the difference before she appeared on the stage that night.[32] Adams was the head of the drama department at Stephens College in Missouri from 1937 to 1949, becoming known as an inspiring teacher in the arts of acting.[13][33]

After her retirement, Adams was on occasion pursued for roles in film. The closest she came to accepting was in 1938, when producer David O. Selznick persuaded her to do a screen test (with Janet Gaynor, who later played the female lead) for the role of Miss Fortune in the film The Young in Heart. After negotiations failed, the role was played by Minnie Dupree. The 12-minute screen test was preserved by the George Eastman House in 2004.[34]

She died, aged 80, at her summer home, Caddam Hill, in Tannersville, New York, and is interred in the cemetery of the Sisters of the Cenacle, Lake Ronkonkoma, New York.[35] Louise Boynton is buried alongside her.[36]

In popular culture

[edit]The character of Elise McKenna in Richard Matheson's 1975 novel Bid Time Return and its 1980 film adaptation, Somewhere in Time (played by Jane Seymour), was based on Adams.[37]

Broadway appearances

[edit]- The Paymaster 1888

- Lord Chumley 1888

- A Midnight Bell 1889

- Men and Women 1890

- The Masked Ball 1892

- The Butterflies 1894

- The Bauble Shop 1894

- The Imprudent Young Couple 1895

- Christopher, Jr. 1895

- The Squire of Dames 1896

- Rosemary, That's for Remembrance 1896

- The Little Minister – 1897 and 1904

- Romeo and Juliet 1899

- L'Aiglon 1900

- Quality Street 1901

- The Pretty Sister of Jose 1903

- 'Op o' Me Thumb 1905

- Peter Pan 1905, 1906, 1912 and 1915

- Quality Street 1908

- The Jesters 1908

- What Every Woman Knows 1908

- Chantecler 1911

- The Legend of Leonora 1914

- The Little Minister 1916

- A Kiss for Cinderella 1916

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Patterson, Ada (1907). Maude Adams: A Biography. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "Famous Stage Actress Biography of Maude Adams".

- ^ Marcosson and Frohman, p. 175

- ^ a b c d e f g h Engar, Ann W. (1994), "Adams, Maude", in Powell, Allan Kent (ed.), Utah History Encyclopedia, Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press, ISBN 0874804256, OCLC 30473917, archived from the original on January 13, 2017

- ^ The 1870 Utah census lists James H. Kiskadden as the head of a household that included his wife, Lucina, and several younger Adamses, perhaps siblings of Lucina. James reported his birthplace as Ohio. The 1880 California census reports James Kisskaden (age 48), Anne Kisskaden (age 29) and Maude Kisskaden (age 7) living in San Francisco. The latter two list their birthplace as Utah.

- ^ a b Cannon, Ramona W. "Woman's Sphere", Relief Society Magazine, September 1953, Vol 40, no. 9, p. 595

- ^ Roberts, Gary Boyd (2020), The Mayflower 500, New England Historic Genealogical Society, p. 268, ISBN 978-0-88082-397-5

- ^ Black, Susan Easton; Woodger, Mary Jane (2011). Women of Character. American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, Inc. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-60861-212-3.

- ^ a b c Hunter, J. Michael (2013). "Maude Adams and the Mormons". Mormons and Popular Culture: The Global Influence of an American Phenomenon. Santa Barbara: Praeger. pp. 135–139. ISBN 9780313391675. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017.

- ^ "Lake Ronkonkoma History, Legends & Myths". Archived from the original on February 4, 2010.

- ^ "Lake Ronkonkoma Historical Society". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ "Annie Adams", Internet Broadway Database, accessed January 20, 2016

- ^ a b "Maude Adams". Collectors Post. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2006.

- ^ a b Marcosson and Frohman, p. 128

- ^ a b "Famous American Actors and Actresses, p. 92". Dodd Mead & Company. 1961.

- ^ Marcosson and Frohman, p. 129

- ^ Marcosson and Frohman, p. 131

- ^ Fields, p. 184

- ^ "Charles Frohman's Leading Theatres". The New York Herald. March 31, 1906. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Felsenthal, Julia (January 20, 2012). "Where the Peter Pan Collar Came From—and Why It's Back". Slate Magazine. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ Dale, Alan (May 9, 1899). "Alan Dale Reviews the Performance". The New York Journal and Advertiser. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Eldridge, Aunt Louisa (May 9, 1899). "Twelve Times the Curtain Rose". The New York Journal and Advertiser. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Bisno, Adam; Ladino, Marie (June 1, 2021). "Out of the Limelight". United States Patent and Trademark Office. Retrieved December 29, 2022.

- ^ "Maude Adams in a Rehearsal of "Joan of Arc" at the Stadium. The New York Times, May 30, 1909

- ^ "The Paducah Evening Sun; excerpt (June 24, 1909)". Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. June 24, 1909. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b Bloom, Ken (December 4, 2003). Broadway. Taylor & Francis. p. 8. ISBN 9780203644355.

- ^ a b Harbin, Marra and Schanke, pp. 15–18

- ^ "Trivia on Famous Stage Actress Biography of Maude Adams". Trivia Library. Retrieved February 7, 2014.

- ^ a b "Maude Adams". Better Days Curriculum. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Allen (1962). The Great White Way: a re-creation of Broadway's golden era of theatrical entertainment. Dutton. p. 107.

- ^ Schanke, Robert A. (May 10, 2004). That Furious Lesbian: The Story of Mercedes de Acosta. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 14. ISBN 0809325799.

- ^ Robbins (1956), p. 219

- ^ Fields, p. 299

- ^ "The Young in Heart". Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Archived from the original on April 22, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ "Long Island Oddities". Archived from the original on September 15, 2008.

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2. McFarland & Company (2016) ISBN 0786479922 In 1898, Adams purchased a farm in Lake Ronkonkoma called Sandy Garth, which in 1922 she donated to the Sisters of St. Regis, and had the Cenacle Retreat House built for them. See Oswald, Keith; Spencer, Dale (2011). Images of America: Lake Ronkonkoma. Arcadia Publishing. p. 88.

- ^ "Legendary sci-fi author tackles social commentary". Deseret News. May 29, 2005. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

References

[edit]- Armond Fields (2004). Maude Adams: Idol of American Theater, 1872-1953. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1927-2.

- Harbin, Billy J.; Marra, Kim; Schanke, Robert A., eds. (2005). The Gay & Lesbian Theatrical Legacy: A Biographical Dictionary of Major Figures in American Stage History in the Pre-Stonewall Era. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472068586.

- Marcosson, Isaac Frederick; Frohman, Daniel (1916). Charles Frohman: Manager and Man. John Lane, The Bodley Head.

- Robbins, Phyllis. Maude Adams: An Intimate Portrait (1956)

Further reading

[edit]- Robbins, Phyllis. The Young Maude Adams (1959)

- Stern, Keith (2009). "Maude Adams". Queers in History. Dallas, Texas: BenBella Books. ISBN 978-1-933771-87-8.

- Jackson, Vicky. "Maude Adams" in Jane Gaines, Radha Vatsal, and Monica Dall’Asta, eds. Women Film Pioneers Project. New York, NY: Columbia University Libraries, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Maude Adams at the Internet Broadway Database

- Maude Adams at IMDb

- "Images related to Maude Adams". NYPL Digital Gallery. held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Maude Adams collection, 1879-1956, held by the Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Maude Adams at Find a Grave

- Maude Adams profile and list of biographies

- Maude Adams in Heroines of The Modern Stage by Forrest Izard, c.1915

- Maude Adams at Better Days 2020, Key Players, 2017.

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Adams, Maude Kiskadden". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Adams, Maude". The Biographical Dictionary of America. Vol. 1. 1906. p. 51.

- "Adams, Maud Kiskadden". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Adams, Maude Kiskadden". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- 1872 births

- 1953 deaths

- American people of English descent

- 19th-century American actresses

- American stage actresses

- 20th-century American actresses

- American lesbian actresses

- LGBTQ Latter Day Saints

- LGBTQ people from Utah

- Actresses from Salt Lake City

- Stephens College faculty

- American women academics

- Women film pioneers